At some point in the development and growth of your practice you will likely feel called to create an altar. An altar represents the physical manifestation of our practice, a reflection of our path and the objects of devotion. Giving them form makes the intangible tangible, and opens up opportunities for creating merit and connecting with what is sacred in our life in ordinary and extra-ordinary ways.

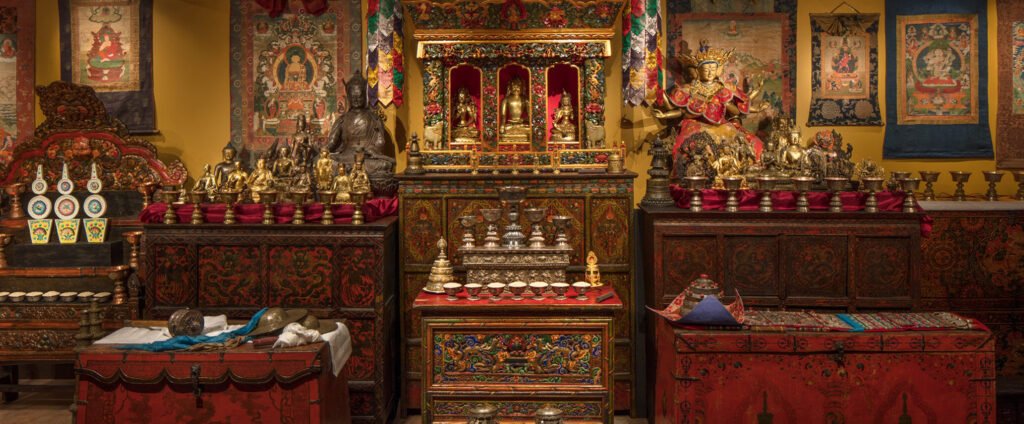

Altars come in all shapes and sizes, from the minimalist to the ornate. This sacred setup is not just physical objects, but represents our practice of the path, a constant and gentle reminder of the path of awakening and compassion.

Why Have an Altar?

At its core, a Buddhist altar is a representation of Buddha’s enlightened body, speech, and mind. The objects on the altar are a visual and symbolic manifestation of the qualities we aspire to develop – wisdom, compassion, generosity, and mindfulness. As practitioners, it becomes a focal point for meditation and a place for making offerings.

Choosing the Right Location

Where are you going to sit each day?

This can change from day to day, but to get started it is beneficial to have a spot to return to. This could be a separate room, your bedroom, basement, or anywhere else that you can have ten to twenty minutes a day without distractions. Put a meditation cushion there, build a small altar, make it a sacred place, make it your own. It doesn’t need to be a whole room, it can be a corner of a room, or a spot next to the window.

No matter where you choose to place your altar, there are a few things to keep in mind:

The chosen spot for the altar should be clean, respectful, and preferably elevated above your seated head level to signify reverence.

If placed in a bedroom, the altar should be near the head of the bed, not at the foot, and positioned higher than the bed. It should not be placed on furniture used for other purposes, like a coffee table or nightstand.

Regardless of its size, the altar should be in a spot where you can sit undisturbed for meditation, ideally for ten to twenty minutes a day. This space should be made personal and special, whether it’s a whole room, a corner, or a spot next to a window.

Altar Essentials

A traditional Buddhist altar embodies the symbols of the Buddha’s enlightened body, speech, and mind. These are typically represented by:

A Statue or Image of the Buddha: Serving as the core of the altar, the Buddha image embodies all three aspects of enlightenment. This can be a statue or a picture, and it forms the central focus of the altar.

Sacred Scriptures: Symbolizing the Buddha’s enlightened speech, these scriptures are an essential element. They should be placed either at the highest point on the altar, directly above the Buddha image, or to its left (which is the Buddha’s right side).

A Stupa: Representing the Buddha’s enlightened mind, the stupa should be situated to the right of the Buddha image (to his left), or beneath the Buddha if the altar has multiple levels.

For more elaborate altars, additional elements can be included:

Other Statues or Images: These may feature root lamas, yidams (tantric deities), dakinis, and Dharma protectors. In such arrangements, the Buddha image should remain central, with other figures placed around it in a balanced manner. If you include a picture of your teachers, those should be place above the Buddha and everything else.

Offerings: To complement these elements, traditional offerings such as seven bowls of water, flowers, incense, and candles are placed on the altar. These offerings are symbolic gestures of devotion and respect to the Three Jewels.

Remember, the arrangement and composition of your altar should reflect a sense of balance and reverence, creating a space conducive to meditation and spiritual reflection.

The Practice of Making Offerings

Making offerings on your altar is a central part of our daily practice. These offerings, which can include water, candles, and food, are symbolic representations of virtues like purity, wisdom, and generosity. It’s essential to make these offerings mindfully and with respect, recognizing the significance of these virtues on the Buddhist path.

The act of making offerings is more than a ritual; it’s a skillful method for accumulating merit. It nurtures the growth of a generosity and diminishes tendencies towards stinginess and selfishness. By making offerings, you sow the seeds for a future of natural, spontaneous generosity.

Offerings should appeal to the five senses – sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch. In Tibetan Buddhism, it’s customary to offer seven bowls of water, symbolizing the seven limbs of prayer: prostrations, offerings, confession, rejoicing, requesting the Buddhas to remain in the world, beseeching them to teach, and dedicating the merits. Common offerings also include flowers, candles or butter lamps, and incense.

When making these offerings, envision that you are offering your good qualities and that they are an expression of your practice. These offerings, while physical, are imagined to fill the extent of space. Offer food with the aspiration that all beings be free from hunger, and water with the hope that all are relieved from thirst. Imagine that the Buddhas receive and delight in these offerings, leading to the enlightenment of all beings.

The arrangement of offerings on the altar is also important. If space allows, arrange them slightly lower than the objects of refuge. For water offerings, prepare at least seven clean bowls, filled each day with fresh water. Arrange these bowls in a straight line, closely spaced but not touching, with the distance between them about the width of a grain of rice. Avoid breathing directly on the offerings.

If you include a butter lamp, position it between the fourth and fifth water bowls. These lamps or candles symbolize the light of wisdom dispelling ignorance.

After setting the water, lighting candles, and placing incense, consecrate the offerings. This can be done by dipping a kusha grass or twig into the water, chanting ‘Om Ah Hum’ (the purifying syllables representing the Buddha’s body, speech, and mind) three times, and then sprinkling the water over the offerings.

Finally, dedication is a key aspect of this practice. Dedicate the merit of your offerings so that all beings may be free from suffering and the causes of suffering, and attain happiness and the causes of happiness.

This dedication magnifies the reach of your offerings, extending their benefits beyond this momentary space and time to the universe.

Maintaining the Altar

The daily upkeep of the altar is an act of devotion. Keeping the space clean and orderly reflects the inner state of the practitioner. Refreshing offerings daily is not just a ritual; it symbolizes a renewed commitment to our spiritual practice each day.

The Ritual of Offerings Removal

At the day’s end, offerings are removed respectfully. At the end of the day, empty the bowls one by one, dry them with a clean cloth and stack them upside down or put them away. Never leave empty bowls right side up on the altar. Water is given to plants, symbolizing the cycle of life and generosity, while food offerings can be shared with animals or consumed, continuing the practice of sharing and kindness. Bowls of fruit can be left on the altar for a few days and can then be eaten when they come down—there is no need to put them outside.

The Altar in Daily Life

Integrating an altar into your daily practice transforms it into a source of refuge and inspiration. It becomes a place for reflection, a reminder of the Buddha’s teachings, and a way to accumulate merit on the path of liberation.

A Buddhist altar is more than a collection of objects; it is a mirror of the Buddhist path. As we set up and maintain our altar from day to day, we nurture our spiritual growth and development, creating a sacred space where we can connect with our buddhanature and the teachings of the Buddha.

Other Resources:

[Soon: Understanding Tantric Ritual Implements]